The Prison Inside Me facility in Hongcheon, South Korea is located about a two-hour drive east of the capital Seoul.

Upon arrival, I’m greeted by the co-founder of the facility, Kwon Yong-seok. He is a former prosecutor, who used to work 100-hour weeks. Kwon tells me the physical and mental toll he endured at his former job were unbearable. It was so painful he would think to himself how great it would be to be locked away for a week.

That’s where the idea sprung up, and in 2008, Kwon and his wife opened the retreat center. Since then, hundreds of people have come to the quiet, serene getaway to find peace and self-reflect.

I’ll be spending the weekend with 19 others “inmates.”

We are given outfits to change into and an orientation session goes over the rules of the facility. No mobile phones. No books. No human interaction.

After a modest lunch and a stroll around the prison grounds, we make our way into our cells. I’ve been designated cell number 212.

The first thing I notice when I enter the room is how small it is. At five square-meters, I can touch both walls with my arms spread out. I scan the room and see a small table with some writing instruments, a kettle and tea set, a yoga mat, a sink tucked in the corner of the room, and a toilet hidden behind a shower curtain. There’s also a panic button to call prison staff in case of emergency.

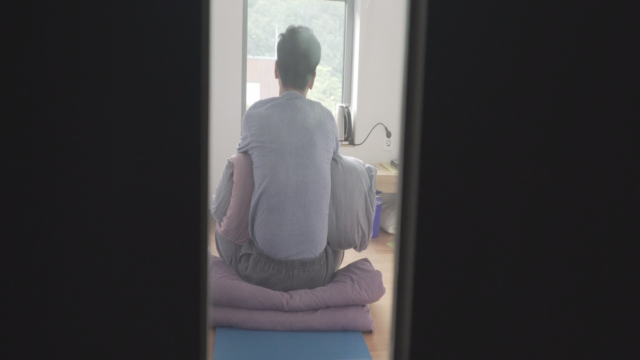

An “inmate” looks out the window of his room at the ‘Prison Inside Me’ facility in Hongcheon, South Korea (CGTN Photo / September 8, 2018)

At 2 p.m. the door to my cell is locked from the outside. I stare out the window and see the sprawling mountains and some clouds lining the bright, blue sky. I spread out the yoga mat and doze off.

At 6 p.m., dinner is pushed through a cubby hole in the door. On the menu is a baked sweet potato and some pieces of fruit.

Silence resonates throughout the room. But the millions of thoughts racing through my head are deafening.

The ‘Prison Inside Me’ complex in Hongcheon, South Korea can house up to 28 people at one time (CGTN Photo / September 8, 2018)

That’s when I decide to try meditation. Emptying my mind of useless thoughts takes effort and concentration. But after about 30 minutes, I begin accepting my current state. Confined in solitude, there is nothing I can do about what’s happening outside my room.

I can’t reply to work emails, accept phone calls, or respond to instant messages. I can’t see the latest on my social media feeds. I don’t know if there’s breaking news happening in some place halfway around the world.

Statistics show South Koreans work some of the longest hours in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. I soon realize why some would go to such extreme measures to escape the stresses of work.

When it’s time for my release at 10 a.m. the next day, I’ve had the best sleep I’ve had in months and I feel an unexplainable inner peace and comfort.

I arrived at prison with countless worries, but I leave realizing the real prison is within me.

![[RTVE] Españoles en conflictos](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/598/096/601x360.crop.jpg?20230809101626)

![[VICE news] SEEKING SOLITUDE | VICE ON SHO](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/283/085/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020950)

![[일조(一条) TV] 5㎡ South Korean Prison-Themed Hotel: No Phone, No Makeup, Centralized Management](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/374/084/601x360.crop.jpg?20210422192920)

![[홍콩 ViuTV] Goodwill Miss Hong Kong](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/483/083/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020951)

![[러시아 RTD] Gangnam Stress - South Korea’s extreme measures against extreme pressure](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/791/074/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020951)

![[CGTN] Assignment Asia: Death, jail and meditation](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/901/071/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020951)

![[The Atlantic] A Weekend in a Prison Cell to Escape Modern Life](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/107/070/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020951)

![[Quartz] Photos: Overworked South Koreans are finding solace in a fake prison](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/093/070/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020951)

![[Reuters] South Koreans lock themselves up to escape prison of daily life](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/087/070/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020952)

![[AL JAZEERA] Prison Inside Me: Providing Koreans peace and solitude in a cell](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/119/069/601x360.crop.jpg?20210418020952)

![[CGTN America] Reporter’s Notebook: Solitary confinement set me free(번역 추가)](https://www.happitory.org/files/thumbnails/016/069/601x360.crop.jpg?20210422193639)